The Consumer Price Index rose a seasonally adjusted 0.3% in June. Excluding the often-volatile categories of food and energy, prices rose 0.1% from May.

The year-over-year increase in all prices was 2.1% in June, and prices excluding food and energy slipped to a 1.9% annual gain in June from 2% in May.

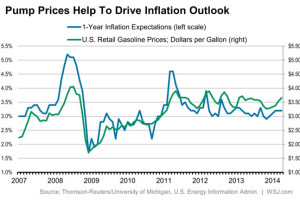

A broad rise in prices during May took the annual inflation rate to 2.1%, its highest level since October 2012. But a 3.3% monthly spike in gasoline prices accounted for most of the June increase as motor-vehicle prices fell, prices for medical services were flat and shelter costs rose 0.2%.

Food prices ticked up just 0.1% in June from the prior month after rising 0.5% in May and 0.4% in each of the prior three months. Drought and livestock and crop disease have caused prices for beef, pork, citrus fruits and other groceries to spike this year, driving the annual increase in food prices from 1.1% in January to 2.5% in May. The annual rise in food prices slipped to 2.3% in June.

(Source: BLS and WSJ)

The adjacent thumbnail gives us a close-up of the trend in YoY Core PCE since January 2012. I’ve highlighted the narrow 12-month range that appears to have been breached to the upside in April.

The adjacent thumbnail gives us a close-up of the trend in YoY Core PCE since January 2012. I’ve highlighted the narrow 12-month range that appears to have been breached to the upside in April.