The Nasdaq index’s year-to-date gain of more than 33% is far outpacing the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s rise of 23% and the 27% rally in the S&P 500. Fueling the Nasdaq’s rally is a hunt by investors to find faster-growing companies in an economy that has yet to show a sustained acceleration.

But unlike the Dow and the S&P 500, which are far into record territory, the Nasdaq remains roughly 20% below its dot-com-era peak. The index hit its all-time high of 5048.62 on March 10, 2000. On Tuesday it closed at 4017.75, up 23 points or 0.58% for the day.

Data showed demand for home building permits jumped 6.2% in October to an adjusted annual rate of 1.034 million, the highest level in more than five years. Economists had projected a rise to a pace of 930,000. The S&P/Case-Shiller 20 City home-price index for September rose 13.3% on the year, slightly better than expectations for it to show a rise of 13%.

The Conference Board’s consumer-confidence index for November unexpectedly fell to 70.4 from 71.2 in October. Economists expected the index to show a rise to 73.0. The Conference Board said uncertainty about future employment and income prospects could make this a challenging holiday season for retailers.

What do you think is driving the markets now?

VS.

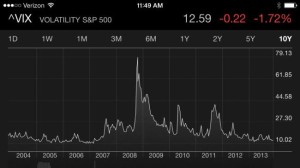

An indicator of Fear is the VIX Index (Implied volatility and/or the amount of “insurance premium” implied by the price of options), which is near its all time lows, as in the chart below (implying investors are complacent or less fearful):

Below is a post from the Chief Economist of First Trust, Brian Wesbury, talking about QE, that resonates with my own thinking on this subject:

The most frequent question we get lately is “what happens to long-term interest rates when quantitative easing ends?” Many analysts argue that the Federal Reserve is buying and holding a huge share of Treasury debt and once QE ends other buyers will suddenly have to absorb more. This will cause interest rates to soar, bust the housing market, undermine stocks, and possibly cause a recession.

We disagree with this analysis in major ways. To respond, we crafted some charts which you will be able to find on our blog, here. In addition, a friend and one of our favorite economists, Scott Grannis at Calafia Beach Pundit, tackled the same topic last week. We urge you to read his take as well.

Much of what people believe about QE is mistaken. It has boosted the monetary base, but not M2. Interest rates are low because of the zero fed funds rate policy, not QE. And most importantly, despite trillions in purchases, the share of Treasury debt held by the Fed is not out of line with history.

Don’t get us wrong. We expect interest rates to move higher in the years ahead, but not because QE ends and not as quickly as the QE-bears say. Until the Fed raises short-term rates, it’s unlikely the 10-year Treasury yield will rise above 4%. QE is a signal of the Fed’s commitment to hold short-term rates near zero, not a direct driver of rates. The longer investors expect the Fed to keep rates near zero, the lower longer-term yields will be. QE itself is not as important as many think.

The Fed has not cornered the Treasury market. The Fed now owns 18% of marketable Treasury debt. This is not an unusually large share; the recent peak was 20% in 2002 and the Fed still held 17% in 2008. Borrowing exploded upward in the Panic, the Fed’s share of debt fell to 8%, but, with QE, it’s back up to 18%. If the Fed still bought $45B/month of Treasuries for the next twelve months – which is very unlikely – we estimate the Fed’s share of Treasury debt would rise to just 21%, slightly above the peak in 2002.

Interest rates have moved in the same direction as the Fed’s share of Treasury debt. Those who see QE as the driver of interest rates have a huge problem – the facts. From late 2007 through early 2009 the Fed’s share of the debt plummeted while interest rates fell. From late 2009 through early 2011, the Fed used QE to push its share back up, but interest rates trended up slightly. From early 2011 through the end of 2012, the Fed’s share of the debt gradually fell. In theory, interest rates should have risen; instead, they fell. So far this year, the Fed’s share of Treasury debt has risen while interest rates have gone up.

Don’t worry; private markets can absorb debt normally. Since 1975, the amount of marketable Treasury debt held outside the Federal Reserve (known as privately-held debt) has increased $9.3 trillion, or $242 billion per year. During this time, annual GDP averaged $8.1 trillion per year. So, on average, the private markets have absorbed Treasury debt equal to 3% of GDP, sometimes more and sometimes less.

If the Fed goes “cold turkey” on QE, but rolls over the debt it already owns, private purchasers of Treasury debt would have to absorb an amount roughly equivalent to the budget deficit, which we forecast to be about 3% of GDP in fiscal year 2014. That’s no different than the long-term average.

More likely, the Fed will taper purchases in 2014 rather than going cold turkey. Assuming the Fed bought $250 billion (about $20 billion per month), private markets would be left to absorb debt equal to about 1.5% of GDP. Easy peasy.

We don’t believe deficits drive interest rates, but for those who do, the idea that QE itself is the driving force behind long-term rates is seriously flawed. The Fed owns no greater share of the debt than normal, and, deficits are shrinking.

While we expect interest rates to head higher, the bottom line is that QE was never that important and ending it is not the Armageddon event that the Bearish clan wants to believe.

The S&P 500 climbed 8.91 points, or 0.5%, to 1804.76. The index is up 27% this year, on pace for its biggest annual gain since 1998, when it climbed 31%. It took more than 13 years for the Index to climb past 1,600 and this year has risen past 1,700 and now 1,800.

An accommodative Federal Reserve, paltry returns in assets such as bonds and steady expansion in corporate profits continue to draw investors to equities. Bulls say the U.S. economy’s expansion—muted as it is—stands out when compared with conditions in other parts of the globe and is liable pick up next year.

Meanwhile, individual investors appear to be regaining comfort with stocks. Mutual funds investing in U.S. shares took in a net $548 million in new cash in the week ended Wednesday, according to fund tracker Lipper, the sixth-straight week of inflows.

Thanks to fracking and shale oil production, the United States is becoming a leading producer of Oil and Gas in 2013, overtaking Russia. Some facts:

- Average oil production in October 2013 was 7.8 mbpd, 19% higher than last year.

- Rising crude supplies from North Dakota’s Bakken shale and Eagle Ford shale in Texas have helped the U.S. become the world’s largest exporter of refined fuels.

- Per EIA, Texas pumped 2.575 mbpd in June-if Texas were its own country, it would rank 15th in the world in terms of oil production.

- The U.S. met 87% of its energy needs in the first five months of 2013 and is on target to hit the highest annual rate since 1986.

- Exports are surging from 1 mbpd in 2006 to 3 mbpd recently.

- Imports are falling from a high of 14 mbpd in 2007 to under 10 mbpd recently. If you take out the re-export of refined products, the Net Imports have fallen even faster to 6 mbpd from 13 mbpd.

Can this declining U.S. net import of Oil and Gas have an impact on the U.S. dollar through its linkages to Current Account Deficits? Generally, a declining Current Account Deficit should be a tail wind for that country’s currency. Also, cheap and abundant natural gas in the U.S. is becoming a competitve advantage to begin bringing offshore production back onshore, which can further impact trade flows and deficits.

Can the once mighty U.S. dollar regain its footing again?

The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed above 16,000 for the first time Thursday, extending a rally that has the blue chip-index on pace for its best year in a decade. With Thursday’s gain, the Dow has advanced 22% so far this year, putting it on pace for the biggest annual rally since a 25% gain in 2003. The blue-chip index is up 144% from its 2009 low. The latest 1,000-point move in the Dow took just 139 trading days, the sixth-fastest 1,000-point gain for the Dow.

Among Dow components, Boeing Co. has led the way higher over the last 1000 points, rallying 40%, highlighting strong demand for commercial aircraft as the global economic recovery takes hold. 3M Company, meanwhile, has risen 20.6% during the same time frame.

This year, all but two of the 30 Dow stocks have gained ground this year except two: Caterpillar Inc. and International Business Machines Corp. and have declined 8.5% and 4.1%, respectively year to date.

Gains on Thursday came after Janet Yellen moved a step closer to becoming the next Federal Reserve leader and a better-than-expected report on the jobs market boosted sentiment.

Behind the broader push that took the Dow through this latest milepost: seemingly greater confidence in the stock market’s ability to withstand a scaling back by the Federal Reserve of the bond-market purchases it has been employing to stimulate the economy. More broadly, bulls point to continued expansion in the U.S. economy and recovery in corporate profits as drivers of the rally. Years of ultralow interest rates have bolstered corporate balance sheets and boards have rewarded investors by buying back stock and boosting dividends.

As such, investors are paying more for stocks relative to the underlying companies’ earnings, making it harder to argue stocks are cheap. The price to earnings ratio for the S&P 500, a broader measure of large U.S. companies’ stocks, stands at about 16.1, up from 13.7 at the start of the year but little above its 10-year average of 15.6, according to FactSet.

The 10 points “represent a broad list of macro themes from our economic outlook that we think will dominate markets in 2014.”

Here they are, with the key quotes pulled from the note.

1. Showtime for the US/DM Recovery

Our 2013 outlook was dominated by the notion that underlying private- sector healing in the US was being masked by significant fiscal drag. As we move into 2014 and that drag eases, we expect the long-awaited shift towards above-trend growth in the US finally to occur, spurred by an acceleration in private consumption and business investment.

2. Forward guidance harder in an above-trend world

Despite the improvement in growth, we expect G4 central banks to continue to signal that rates are set to remain on hold near the zero bound for a prolonged period, faced with low inflation and high unemployment. In the US, our forecast is still for no hikes until 2016 and we expect the commitment to low rates to be reinforced in the next few months.

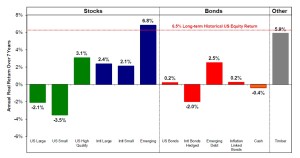

3. Earn the DM equity risk premium, hedge the risk

Over the past few years, we have seen very large risk premium compression across a wide range of areas. While not at 2007 levels, credit spreads have narrowed to below long-term averages and asset market volatility has fallen. Even in a friendly growth and policy environment such as the one we anticipate, this is likely to make for lower return prospects (although more appealing in a volatility-adjusted sense). In equities, in particular, the key question we confront is whether a rally can continue given above-average multiples. We think it can.

4. Good carry, bad carry

Our 2014 forecast of improving but still slightly below-trend global growth and anchored inflation describes an environment in which overall volatility may justifiably be lower. Markets have already moved a long way in this direction, but equity volatility has certainly been lower in prior cycles and forward pricing of volatility is still firmly higher than spot levels. In an environment of subdued macro volatility, the desire to earn carry is likely to remain strong, particularly if it remains hard to envisage significant upside to the growth picture.

5. The race to the exit kicks off

2013 has already seen some EM central banks move to policy tightening. As the US growth picture improves – and the pressure on global rates builds – the focus on who may tighten monetary policy is likely to increase. As we described recently (Global Economics Weekly 13/33), the market is pricing a relatively synchronised exit among the major developed markets, even though their recovery profiles look different. Given that the timing of the first hike has commonly been judged to be some way off, this lack of differentiation is not particularly unusual. But the separation of those who are likely to move early and those who may move later is likely to begin in earnest in 2014.

6. Decision time for the ‘high-flyers’

A number of smaller open economies have imported easy monetary policy from the US and Europe in recent years, in part to offset currency strength and in part to compensate for a weaker external environment. In a number of these places (Norway, Switzerland, Israel, Canada and, to a lesser extent, New Zealand and Sweden), house prices have appreciated and/or credit growth has picked up. Central banks have generally tolerated those signs of emerging pressure given the external growth risks and the desire to avoid currency strength through a tighter policy stance. As the developed market growth picture improves, some of these ‘high flyers’ may reassess the balance of risks on this front.

7. Still not your older brother’s EM…

2013 has proved to be a tough year for EM assets. 2014 is unlikely to see the same level of broad-based pressure. The combination of a sharp downgrade to expectations of China growth and risk alongside the worries about a hawkish Fed during the summer ‘taper tantrum’ are unlikely to be repeated with the same level of intensity.

8. …but EM differentiation to continue

2013 saw countries with high current account deficits, high inflation, weak institutions and limited DM exposure punished much more heavily than the ‘DMs of EMs’, which had stronger current accounts and institutions, underheated economies and greater DM exposure. This is still likely to be the primary axis of differentiation in coming months, but in 2014 we would also expect to see greater differentiation within both these categories.

9. Commodity downside risks grow

Last year we pointed to the ongoing shift in our commodity views, ultimately towards downside price risk. The impact of supply responses to the period of extraordinary price pressure continues to flow through the system. And we are forecasting significant declines (15%+) through 2014 in gold, copper, iron ore and soybeans. Energy prices clearly matter most for the global outlook. Here our views are more stable, although downside risk is growing over time and production losses out of Libya/Iran and other geopolitical risk is now playing a large role in keeping prices high.

10. Stable China may be good enough

Expectations of Chinese growth have reset meaningfully lower as some of the medium-term problems around credit growth, shadow financing and local governance have been widely recognised over the past year. Some of these issues continue to linger: the risks from the credit overhang remain and policymakers are unlikely to be comfortable allowing growth to accelerate much. But the deep deceleration of mid-2013 has reversed and even our forecast of essentially flat growth (of about 7.5%) may be enough to comfort investors relative to their worst fears.