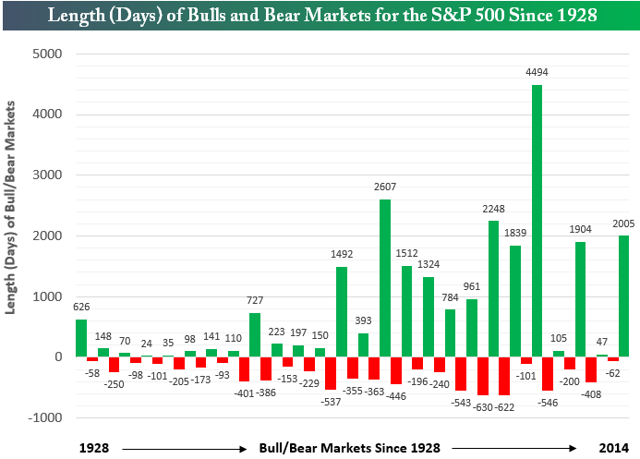

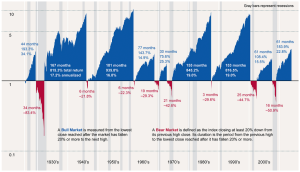

The difficult market environment in August reminded us about the three other Augusts – August 1997 (Asian crisis), August 1998 (Russian crisis) and August 2011 (European debt crisis). In each of those episodes, there were some type of global risk events, and as a result, US market suffered significantly.

In 1997, Asian financial crisis started in Thailand with the collapse of the Thai baht after the Thai government was forced to cut the Thai baht’s peg to US dollar after exhausting its foreign reserve. As the crisis spread to Indonesia, South Korea and Malaysia, most of Southeast Asia and Japan experienced declining currencies, stock markets crashes and a jump in private debt. The crisis raised the fears of global economic meltdown. As a result, the US equity market dropped by 5.6% in August. However, the US market recovered quickly with a 5.5% rally in September.

In 1998, the Asian financial crisis and the following reduced demand for crude oil and nonferrous metals, negatively impacted the Russian exports and foreign reserves. A series of political missteps and inability to implement a set of economic reforms severely erased investor confidence and led to capital flight. Without enough foreign reserve to support its currency, on 17 August 1998, the Russian government devalued the ruble and defaulted on domestic debt. The Russian default caused global liquidity dry up and credit spreads widen, which brought down the then-known hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management. US equity markets tumbled 14.4% in August, but again recovered nicely in September and October.

In 2011, the European debt crisis intensified after it started in the wake of the Great Recession around late 2009. In August, the government bond yields in Italy and Spain breached 6% level as the European leaders struggled to reach an agreement to expand the bailout fund. The US equity market dropped by 12.4% during the months of August and September. However, once again, it recovered in October, gaining 10.9%.

This year, the stock market rout started in China when the Chinese government unexpectedly devalued its currency, which triggered concerns over global economic slowdown. The US equity market declined by 6.1%.

| Event | S&P 500 Index

(August) |

S&P 500 Index

(whole year) |

Valuation (current PE) | Short Term Interest Rate | ISM Manufacturing Index |

| 1997 -Asian Crisis | -5.6% | 33.4% | 21.9 | 5.2% | 56.3 |

| 1998 – Russian Crisis | -14.4% | 28.6% | 22.0 | 4.8% | 49.3 |

| 2011- European Debt crisis | -12.4% (Aug and Sept) | 2.1% | 13.6 | 0.0% | 50.6 |

| 2015 – Chinese Slowdown | -6.1% | ?? | 18.6 | 0.0%

|

51.1 |

The equity market drops in the first three crises all recovered nicely and quickly. Will this time be the same? We believe it is quite likely though we still recommend caution.

- There is no crisis this time so far. The Chinese economy will definitely or has already slowed down from double digit to 7% or lower. But everyone tends to agree that it will grow at a reasonable pace. The Chinese stock market rout started after a dramatic run-up and a bubble-level valuation. The sell-off, though painful, was a necessary correction. As a word of caution, the bad news from China may not be over, we may see more market volatility going forward.

- The US equity valuation is not cheap, but not at an extreme (see table above). During the crises in 1997 and 1998, the equities are much more expensive.

- The US monetary policy is ultra-loose. Even if the Fed may raise interest rates this year, the monetary policy is still very accommodative. The interest rates in 1997 and 1998 were much higher.

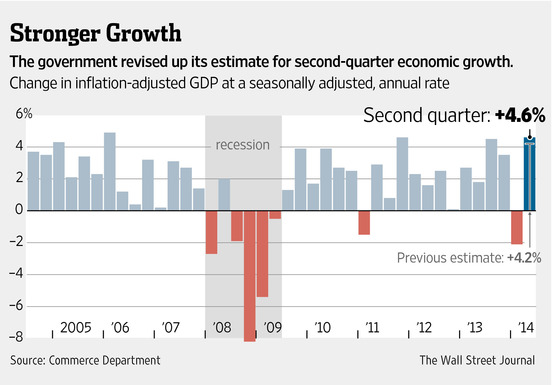

- The US economy is solid. In Q2, the US economy grew at 3.7% annual pace. ISM Manufacturing Index is still in expansion territory and unemployment rate is close to 5%. The slowdown in China will have limited impact on the US growth as the exports to China only account for 1% of the GDP in the US. However, the slowdown in China will have significant impacts on the US companies that are doing businesses there.

(Source: Julex Capital)